Introduction and Overview

THE DRUG CRISIS IN AMERICA

Prevention

Essential Elements of Good Drug Policy

Drug policy must be informed by science, data, and evidence-based practices. It must also produce positive outcomes for both users and nonusers alike. For families. Communities. And, of course, individuals. Good policy must be free from political influences that contradict science and presented in a format accessible to decision-makers and the public.

The United States is facing an unprecedented drug crisis. According to the CDC’s WONDER database, the number of overdose deaths increased from 16,849 in 1999 to 105,007 in 2023, rising 523%. Provisional estimates from the CDC’s NVSS database indicate that there were 89,740 overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending in August 2024, suggesting that overdoses have begun to decline as the nation emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic. The overdose death rate for 14- to 18-year-olds has increased to approximately 5 deaths per 100,000, representing more than 20 teen deaths a week.

There is reason to be cautious about this decline; an FDPS-affiliated Viewpoint in the Journal of the American Medical Association pointed out that the decline in overdose deaths between 2017 and 2018 was nevertheless associated with a continued increase in the number of disability-adjusted life years lost to drugs. Policymakers should aim to reduce the drug-attributable burden of harm, not only the number of overdose deaths.

To bend the curve of the drug crisis, policymakers must advance a new drug policy that draws on the lessons of the past and is grounded in the best available evidence.

The current drug epidemic has evolved through three stages and is now entering a fourth. The first involved prescription opioids, such as Oxycontin, and expanded between the late 1990s until about 2010. During that time, prescription drugs were overprescribed to patients and pharmaceutical companies heavily promoted them as non-addictive solutions for pain management. Some doctors operated what became known as “pill mills,” where individuals without a medical need could purchase prescriptions for opioids. Prescription opioids were relatively easy to obtain, and rates of addiction rose accordingly.

United States Overdose Deaths

1999

2023

Rising 541%

Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids and stimulants*

2015

2023

*Defined as overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl; ICD-10 code T40.4) and either cocaine (T40.5) or psychostimulants with abuse potential (primarily methamphetamine; T43.6).

In response, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) introduced prescription drug monitoring programs, which helped to identify “pill mills” and individuals who were going to multiple doctors. Purdue Pharma, the maker of Oxycontin, came under increased scrutiny. As prescription opioids became better regulated and more difficult to obtain, users turned to the illicit market, where they were met with a supply of heroin. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of heroin-involved overdoses quintupled from 3,036 to 15,482. The increased use of heroin constituted the second wave of the opioid epidemic.

Soon thereafter, heroin was replaced by fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin, marking the third and current wave. Synthetic opioids other than methadone––primarily fentanyl––accounted for 782 overdose deaths in 2000, 3,007 in 2010, 56,516 in 2020, and 72,776 in 2023. Fentanyl has made the drug crisis exponentially worse.

Now, fentanyl is being increasingly co-used with stimulants. Between 2015 and 2023, the number of overdose deaths that involved a synthetic opioid other than methadone (primarily fentanyl) alongside either cocaine or methamphetamine increased from 1,969 to 41,583. This trend has led to what many foresee to be the fourth wave of the opioid epidemic.

However, despite the increase in opioid-involved overdose deaths, the prevalence of opioid use has decreased in recent years. Between 2015 and 2023, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the number of past-year opioid users decreased from 12.69 million to 8.90 million, while the number of past-month users decreased from 3.96 million to 2.44 million.

Though opioid use has decreased, the use of other drugs has been increasing. The number of cocaine users increased from 4.83 million in 2015 to 5.01 million in 2023, while the number of methamphetamine users increased from 1.71 million to 2.62 million and the number of hallucinogen users increased from 4.69 million to 8.80 million. Likewise, the number of marijuana users increased from 36.04 million in 2015 to 61.82 million in 2023.

Beyond this, many users are now polydrug users, meaning that those who misuse one drug are more likely to misuse an additional substance as well. Combining drugs often provides a more intense “high,” but sometimes drugs are used together to counteract the effects of one of the substances. Though some initially wondered whether marijuana and alcohol would act as substitutes, particularly for young adults, they are now viewed as complements, with individuals using more of both.

While usage rates among adults have generally been increasing, with the exception of opioids, usage rates among youth have been trending downward. According to the NIDA-funded Monitoring the Future study, the percentage of 12th graders who used “any illicit drug” decreased from 53.1% in 1980 to 32.5% in 1990, before increasing to 40.9% in 2000, going to 38.3% in 2010 and down to 26.2% in 2024.

Though some estimates highlight diverging trends in the rates of youth use, highlighting the effectiveness of prevention efforts, there are also causes for concern. Between 2020 and 2023, based on the DSM–V criteria used by the NSDUH, the number of 12–17-year-olds that had a cannabis use disorder increased from 1.01 million to 1.23 million. At the same time, perceptions of risks about drug use have declined––a low perception of risk is a risk factor and predictor for use. According to the Monitoring the Future survey, the percentage of 12th graders that said there is great risk associated with using marijuana regularly declined from 78.6% in 1991 to 35.9% in 2024. The percentage of 12th graders that said there is great risk associated with trying LSD once or twice decreased from 48.6% in 1991 to 29.4% in 2024.

Daily marijuana use in the past year

2011

2023

12–17-year-olds With Cannabis Use Disorder

2020

2023

In 2023, 27.15 million Americans aged 12 and older have a drug use disorder*

*The sum of the respective categories exceeds the total number of Americans with drug use disorder because some individuals have more than one condition.

As more people use a certain drug, more inevitably misuse it. In 2023, 27.15 million Americans 12 or older had a drug use disorder, up from 24.48 million in 2021. In 2023, of these, 19.16 million had a marijuana use disorder, 5.68 million had an opioid use disorder, 1.78 million had a methamphetamine use disorder, and 1.26 million had a cocaine use disorder.

Alongside rising rates of overdoses and substance use disorders, there has been an increase in drug- related emergency department visits, according to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, which was discontinued in 2014 and reinstated in 2022. In 2023, there were 7,590,202 drug-related ED visits. There were 3,114,472 alcohol-related ED visits in 2023, up from 2,996,516 in 2021. The number of marijuana-related ED visits increased from 804,285 in 2021 to 896,418 in 2023. And there were approximately 277,690 fentanyl-related ED visits in 2023, up from 123,563 in 2021.

Despite concerning increases in drug use, drug use disorder, drug-related emergency department visits, and overdose deaths, there has been a decrease in treatment admissions for most drugs, indicating that millions of Americans are not receiving the help they need. Between 2020 and 2022, the most recent year for treatment data, the number of treatment admissions declined from 1,568,291 to 1,498,034. Treatment admissions for opiates decreased from 406,088 to 355,180, while admission for marijuana decreased from 145,115 to 122,049. Admissions for cocaine increased from 74,244 to 77,034, while admissions for methamphetamine increased from 181,350 to 181,747.

Put together, these drug- related harms and rising rates of drug use highlight the vital importance of demand reduction, which includes prevention and treatment. At the same time, supply reduction efforts play a vital role in drug control policy.

– NSDUH

Supply reduction operations aim to disrupt the production, distribution, and sale of illicit drugs. By focusing on all aspects of the supply chain, law enforcement agencies seek to

disrupt the supply of drugs and increase their prices, which will ultimately lower the prevalence of their use. Given that the drug trade has become increasingly globalized, U.S. efforts must work with international allies and invest in capacity building. Neither demand reduction, supply reduction, or harm reduction interventions will work perfectly, highlighting why interventions across the continuum are necessary.

Though much of this report focuses on illicit drugs, it is important to note that legal, regulated prescription drugs also contribute to the drug crisis, as we saw with prescription opioids in the early 2000s. Some may develop a substance use disorder when using medications as prescribed by their doctor. Progress has been made in the overprescription of opioids, yet similar issues are now arising with Adderall, a stimulant prescribed for ADHD. Prescription drugs are also diverted to the illicit market, where they are resold to individuals for misuse or for purported self- medication, which presents additional health-related risks to users.

Harm reduction represents a strand of drug policy that seeks to reduce drug-related harms. It is both an intervention and a philosophy within drug policy, but its goal should always be recovery from drug use. A few long-standing harm reduction interventions, which are supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, include the distribution of naloxone and syringe programs that lead people to treatment. However, part of this movement has rushed beyond its evidence base, with activists now calling for unproven policies like “safe supply” and “safe consumption sites.” While current evidence does not show that these interventions are effective, more research is required to understand their potential consequences.

The public and policymakers can be forgiven for wanting to try something new. Overdose deaths have surpassed 100,000 each year, and many are rightly concerned about inequities in the criminal justice system and are exasperated by poor outcomes. These lessons from the past remind us of the importance of ensuring that equity is woven throughout all our drug policies and interventions. Rather than carving out equity as a single policy or focus below, we find that its theme and intentions should be considered in all drug policy decisions, from prevention and treatment to criminal justice reforms and grant funding. Equity is a value, not a specific policy, that underlies our approach to drug policy.

Policymakers must work proactively to expand the reach of evidence-based prevention and treatment programs and strategies, while working to reduce the supply of illicit drugs. But before policies can be implemented, policymakers must be educated about them and the related issues. To help them achieve these ambitious goals––and ultimately save lives––the Foundation for Drug Policy Solutions has crafted this Blueprint for Effective Drug Policy, which can serve as a dynamic guide to good drug policy.

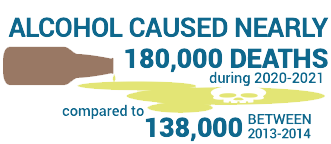

Two readily available substances also take a significant toll on public health every year: tobacco and alcohol. Following decades of counter-advertising campaigns, stricter policies, and excise taxes, the prevalence of tobacco use has declined. Still, tobacco kills more than 480,000 people every year and is the top preventable cause of death in the United States, according to the American Lung Association. Likewise, the CDC found that alcohol caused nearly 180,000 deaths each year during 2020-2021, compared to 138,000 during 2013-2014. After decades of their normalization––often fueled by the industries that produced and profited from them––public health leaders have finally begun to recognize their harms and have taken steps to reverse them. The harms of these substances, particularly tobacco, should serve as cautionary tales against the legalization, normalization, and commercialization of other substances. But in many circles these warnings have gone unheeded.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 24 states have legalized recreational marijuana and 38 have legalized medical marijuana at the time of publication. To be sure, marijuana remains illegal at the federal level––it is a Schedule 1 substance, meaning it has a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical benefit. Despite claims about its therapeutic benefits, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved marijuana for the treatment of any disease or condition (even though two marijuana-based components are in a handful of FDA-approved medications). Even so, the legalization and commercialization of marijuana––and thus, the normalization of this drug––continues to threaten public health and public safety.

These changes have been occurring within a drug policy landscape that has been evolving and threatening to exacerbate the drug crisis. In 1996, California became the first state to legalize so-called “medical marijuana.” This was followed in 2012 by the legalization of recreational marijuana by Colorado and Washington, in defiance of federal drug laws that maintained that marijuana was a Schedule I substance with a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical benefit. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved marijuana for the treatment of any disease or condition. Because the federal government has taken a hands-off approach to issue, states have been able to legalize marijuana without legal consequences.

The state-level legalization of marijuana opened the door to the normalization of drug use and the legalization of other drugs, notably psychedelics. In 2020, Oregon became the first state to legalize psychedelics for medical use. Colorado followed suit in 2022. Notably, in 2020, Oregon decriminalized the possession of all other drugs. This policy faced public backlash and resulted in rising rates of crime and overdoses, so the state recriminalized the possession of drugs in 2024. These initiatives normalize these substances and reduce associated risk perceptions, which are associated with increases in experimentation and use.

A central theme of these state-level reforms is their backing by well-funded special interest groups, such as the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA), which do not have public health as their overarching goal. The DPA, for example, wants to end all drug enforcement, drug testing, accountability-based treatment, and legalize all substances, no matter the consequences. These policies threaten to either undo and reverse progress made, including with the reduction in youth use, or to exacerbate the issues facing our country by contributing to more overdose deaths and a higher prevalence of substance use disorder. Public health organizations are often outfunded and cannot compare head-to-head against these organizations.

A related issue is that these policies often commercialize drugs and lead to the creation of new industries, whether they are profit-driven companies selling marijuana or psychedelics. Stemming from the concept of commercial determinants of health, these industries will pursue their profits and use their vast resources to advance their self- interest, which is at direct odds with public health and overall well-being. The marijuana industry is producing and promoting increasingly potent products to maximize its bottom line, while opposing regulations that would protect vulnerable populations. This is one reason why marijuana and its harms have been rising so steadily.

In 2011, the year before Colorado and Washington became the first states to vote to legalize recreational marijuana, 29.73 million Americans 12 or older were past-year users of marijuana, or 11.5% of this population. By 2023, this had doubled to 61.82 million Americans, or 21.8% of those 12 or older. Similarly, the number of Americans that were past-month users of marijuana, which is a measure of heavier use, increased from 18.07 million to 43.65 million, rising from 7.0% of the population to 15.4%. The number of daily or almost daily marijuana users in the past year increased from 4.98 million in 2011 to 15.74 million in 2023, or 1.9% of those 12 or older to 5.6%. While more Americans are using marijuana, the most concerning increases are among the heaviest users.

representing approximately

use disorder increased to 42.3%

or more than 4 in 10 USERS.

The number of marijuana-related ED visits increased from 804,285 in 2021 to 896,418 in 2023. These events range from an individual getting too high, to a toddler consuming a package of their parent’s edibles, to someone experiencing cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

More marijuana users are also driving under the influence of this drug. Between 2021 and 2023, the number of Americans 16 or older that self-identified as driving under the influence of marijuana increased from 10.88 million to 12.14 million. In 2023, 20.0% of past-year marijuana users over the age of 16 drove under the influence of marijuana, compared to 11.6% of past-year alcohol users over the age of 16 who drove under the influence of alcohol. Of note, this data from drivers who self-identified as driving under the influence includes those who drove under the influence of only THC, as well as those who used multiple drugs alongside THC, though the latter is far more dangerous. A 2022 report from the National Traffic Safety Board noted that marijuana is the second most commonly detected substance after alcohol in arrests for impairment and crashes.

A leading concern with legalization is that it has ushered in a for-profit marijuana industry, which works to maximize its profits at the expense of public health. The marijuana industry, following the playbook of the tobacco industry, has worked to produce and promote ever-stronger products, which are increasingly addictive and linked to a range of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, psychosis, and even a loss of IQ.

Supporters also assured skeptical voters that legalization would displace the illicit market, yet the opposite has occurred, seeing an expansion of the underground market in “legal” states.

In October 2022, President Joe Biden directed the Department of Health and Human Services to review marijuana’s schedule. The Department, through the FDA, ultimately recommended that marijuana be placed in Schedule 3, indicating that marijuana has a lower potential for abuse and medical benefits. However, the FDA’s review broke from decades of precedent for determining the appropriate schedule of a drug. Following this recommendation, the Drug Enforcement Administration initiated its own review of marijuana. As of February 2025, a final determination from the DEA has not been made about marijuana’s schedule.